Kenya 2022

by Dr Hanin Hamza

I’m a trainee in Anaesthesiology and I’m currently taking leave out of the SAT programme, between SAT 2 and SAT 3. I feel immensely privileged to be able to take this time away to forge new experiences. In November this year, I travelled to Kenya with a medical non-profit charity organisation called Global Emergency Care Skills (GECS). GECS was founded in 2008 by Prof. Jean O’Sullivan, consultant in Emergency Medicine at Tallaght University Hospital, with the purpose of providing training courses to healthcare staff in low and middle-income countries.

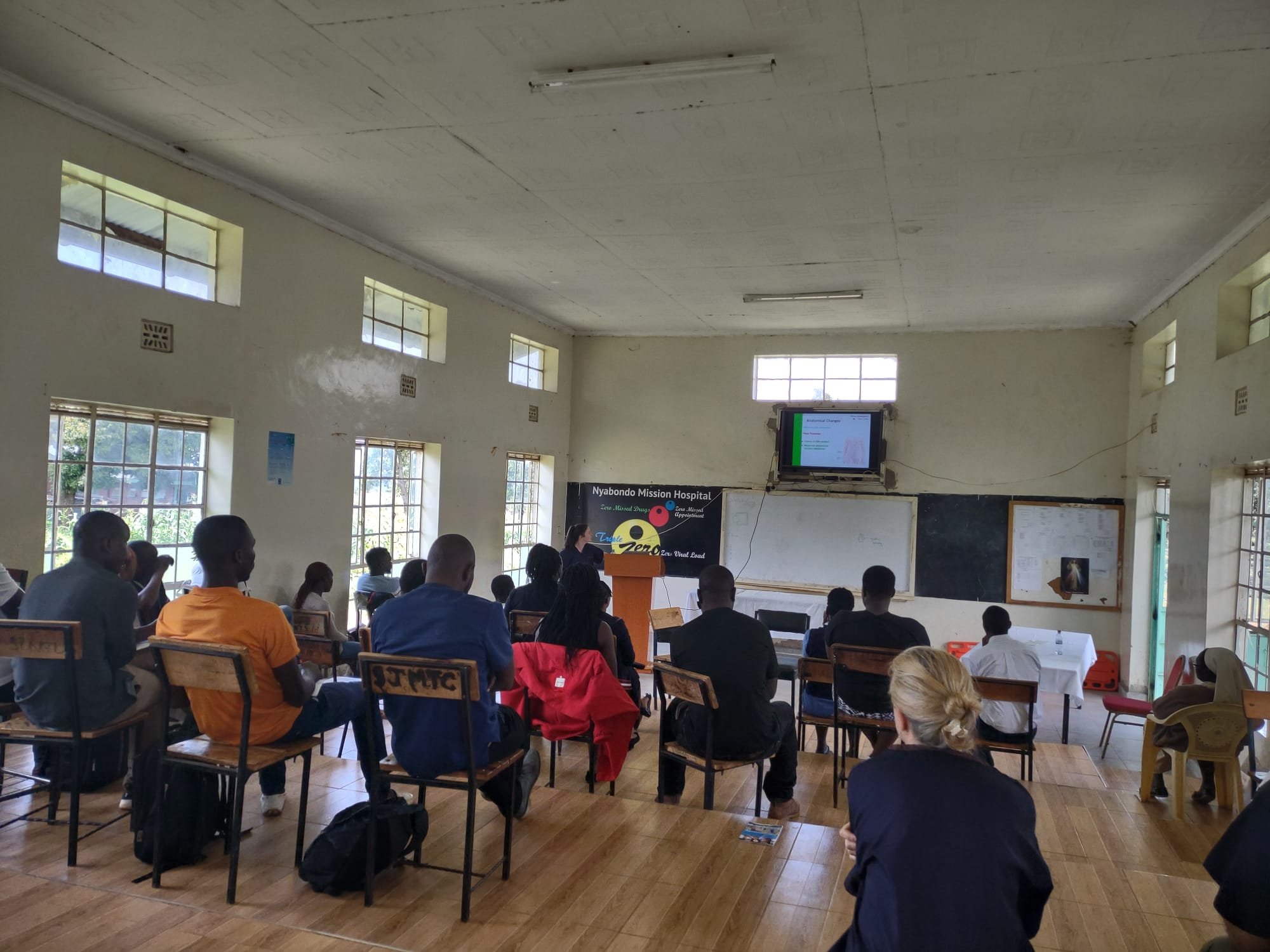

The GECS faculty was led by Prof. Jean O’Sullivan and Dr. Robert Eager and was otherwise composed of another trainee in Anaesthesiology, Siobhán Clarke, Emergency Medicine consultants and trainees, a medical trainee and a transition year student on work experience. Together we visited St. Joseph’s Nyabondo Missionary Hospital in Nyabondo, Kenya. There we delivered a 5-day training course focusing on the management of medical emergencies and trauma, using a combination of didactic teaching and simulation training.

St. Joseph’s Nyabondo is, at present, an 80-bed hospital with an emergency room, inpatient wards, a maternity ward, laboratory services and an operating theatre. Additionally, the hospital provides outpatient services such as nutritional services, HIV care and reproductive health education. Alongside other rural hospitals, St. Joseph’s Nyabondo serves the surrounding 6 counties with a combined population of approximately 4 million people. We were invited to teach at St. Joseph’s Nyabondo because in the coming months, a new Trauma Centre is due to be opened on the site. The hospital director wrote to medical charities, one of whom was GECS, requesting emergency and trauma training provision for staff in St. Joseph’s Nyabondo and neighbouring hospitals.

I was surprised to learn upon our arrival, that very few of the staff undertaking the course (and managing emergencies in St. Joseph’s Nyabondo on a daily basis) were doctors. In fact, there are only 3 doctors contracted to work in the entire hospital regularly, 2 of whom (ideally) would be on-site in a given 24 hour period. There is a paucity of medical graduates throughout Kenya and much of Africa, therefore many of the tasks that would be carried out by doctors back home would instead be performed by clinical officers or nursing staff. Clinical officers complete a 3 year university degree and are employed in a role similar to doctors however with a limited scope of practice. Of the 35 course participants, 2 were doctors and the remainder were a mix of clinical officers and nurses.

The course that we delivered was based around the World Health Organisation’s Basic Emergency Care course. Given the imminent upgrade of St. Joseph’s Nyabondo into a regional Trauma centre, we also chose to emphasise trauma management, dedicating 2 days of the course to delivering trauma lectures designed by the GECS group and conducting trauma simulation sessions. Additionally, throughout the course we were able to incorporate airway teaching.

I found it incredibly touching how motivated each and every person who attended the course was. Keeping lectures and simulation sessions within their allotted time was difficult due to the sheer number of questions the attendees had. It was very apparent how much they valued this opportunity for learning. The hospital security staff were also keen to take an opportunity to up-skill, eagerly partaking in a workshop on the safe immobilisation and transport of the trauma patient. Later in the week speaking to Kennedy, one of the doctors

participating, I found out that healthcare workers in Kenya usually have to take unpaid leave from work to attend any educational courses and in fact, this had precluded many members of staff from other hospitals who had signed up from actually attending this course.

Not keen on disproving the Anaesthetist stereotype, as soon as we arrived at St. Joseph’s Nyabondo, Siobhán and I were hoping to get a tour of the operating theatre. We were soon introduced to Chris, a clinical officer specialising in Anaesthesiology, who is the only member of the Anaesthesia team based in St. Joseph’s Nyabondo full-time. There is also an Anaesthetist (a doctor) available at times for procedures in theatre and he works between several hospitals in the region. However, hearing from Chris (and seeing the theatre logbook) the ‘Anaesthetist’ is most often not a doctor. Chris showed us around the theatre and talked us through the equipment and medications available to him. Suffice to say, anaesthetic practice in rural Kenya is an exercise in doing quite a lot with very little.

On the Wednesday of our week in Nyabondo, Siobhán and I were invited to observe an emergency Caesarean section, with the mother’s consent. A significant proportion of deaths at St. Joseph’s Nyabondo are due to maternal and neonatal causes with 54% of deaths in this hospital attributed to communicable, maternal and neonatal disease. In theatre, Chris explained to us that he performs low dose spinals for Caesarean sections unless contra-

indicated. However, he clarified that availability of vasopressors in the hospital is severely limited and that he has no access to phenylephrine, ephedrine or noradrenaline. Notably, there is no neonatal resuscitation station in the theatre. We watched the surgery with bated breath. Mother and baby came through and when Siobhán and I visited them on the maternity ward the next day, they were thriving. The unfortunate reality is that that is too often not the case and unsurprisingly in the course feedback, participants requested training in Obstetric emergencies in future.

After teaching was finished on our third day, we visited the Nyabondo Centre for Persons with Disabilities. As Sr. Ludavena led us through the centre, I was struck by how the religious sisters took their passion for helping the disadvantaged and built a loving home for children with disabilities, many of whom had been abandoned by their families and society. Sr. Arnolda, a nurse who now works in an antenatal clinic told me: “this is still where my heart is”. As well as being a home, the centre has teamed up with AMREF, the Flying Doctors of East Africa, to perform Orthopaedic and Reconstructive surgeries that change the lives of their children. The centre in Nyabondo provides rehabilitation services with charity funded-physiotherapy, occupational therapy and even production of prostheses on-site. Additionally, the sisters provide vocational training in the centre, teaching skills that can enable their children to live independent adult lives. A description can’t fully encapsulate the feeling of being there and seeing the impact that the co-ordinated work of medical charities can make to a community or a group of people in need

I feel so fortunate to have had the experience of travelling to Kenya with GECS. Reflecting on my experience now, I feel like a naïve version of myself boarded the plane in Dublin airport, knowing that we were headed to an under-resourced African hospital but not having a frame of reference for it. The week was a steep learning curve. The entire GECS faculty showed an immense amount of versatility, adapting the course along the way to ensure that the knowledge imparted could be put to real-world use by participants with the resources available to them.

It was so fulfilling hearing and reading feedback from the people who attended the teaching sessions. At the close of the course one of the participants, Mike, gave an emotional speech to thank both the GECS faculty and those who attended. He reflected on previous practice in their various hospitals and opined that the training that we provided, such as a systematic (ABCDE) approach to managing emergencies will help to save lives in future. It was a particularly poignant moment in my week that I’m not embarrassed to say brought tears to my eyes. A nurse who attended the course, Denis, summarised: “As per now, I am very confident I can manage a patient in trauma. I have the capacity”.

Close to my heart (and I’m sure to Siobhán’s) was the airway teaching and simulation component of the course. Siobhán delivered an airway lecture at the outset of the course. Over the following days, together we conducted airway simulation sessions in small groups which proved very popular with the course participants. Notably, in a questionnaire designed by the GECS group, 58% of the attendees indicated that they had no previous airway training however 63% had been involved in clinical situations which required emergency airway management. The happy ending to this story is that 100% of attendees reported feeling more confident in their airway skills following this GECS course.

One key aim of the GECS group was to ensure that sustained teaching and delivery of life-saving skills could continue in future. As part of this effort, the 5th and final day of the course was devoted to training the trainer. Course lectures were made available to the hospital’s clinical director and the equipment and mannequins donated by GECS will make simulation training possible into the future at St. Joseph’s Nyabondo.

Prayer and gratitude were all around us in Nyabondo. The course began and ended with staff nurse Rose leading the attendees in prayer, to thank God for granting them this opportunity for learning. I’m thankful for the people who volunteered to join the GECS faculty and the wonderful group that I got to meet and work with. I’m thankful for the friends, family, hospitals and businesses in Ireland that donated money and equipment to make this trip possible. I will be more appreciative in future for the training opportunities I have in life, for the mentorship and guidance that’s so readily available to me, for end-tidal CO2 monitoring in theatres, and for working in hospitals that can afford propofol, vasopressors, a defibrillator and more than one laryngoscope. I’m so grateful for the fulfilment and the personal growth this trip with GECS has given me and I would thoroughly recommend the experience to anyone who is tempted by the prospect.

Printed with consent of the author.